I, perhaps famously, introduced my parents to Yelp this summer on the way back from our annual North Carolina beach trip by suggesting we have lunch at The Ten Top in Norfolk, VA before heading to the airport to return home. The review instructing me to get the Turkey Apple Club on cinnamon bread and suggesting that the pasta salad was especially good sold me enough to sell my parents. It worked out wonderfully, and is actually my favorite part of the whole trip. That may be because I was raised on going out to eat, and it was one of two restaurants featured on the trip, and certainly it was the better one. A fond memory thanks to strangers on the internet, organized by Yelp.

I use Yelp frequently. In my Wednesday Night Dinner group, where we try a new restaurant most every week, picking a restaurant and sending it out to the group often is done via a one line email with a yelp URL and a time. I don’t know why we still include the time, its always 7:30; the only important information in the email is the Yelp URL. Every member has their own method of picking places, some uses sources other than yelp, as do I. I often use local reviews like this one for last week’s delicious pick, L’Impasto, but I always check the Yelp reviews as well. In fact, the reviews for L’Impasto were so good, and so few in number that I considered the possibility that they were fake. If they were fake, they were at least correct in this case.

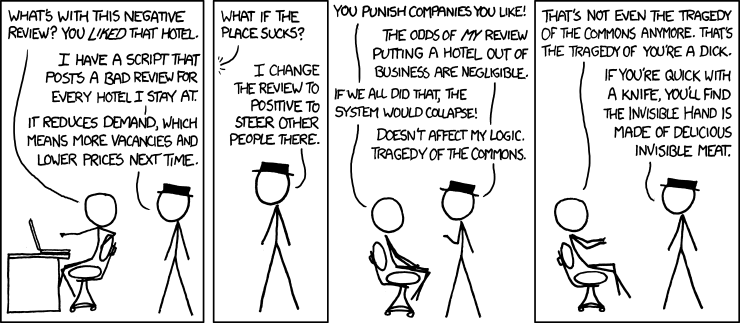

Yelp might review Hotels, they do review places that are not restaurants, but I certainly have never looked at those reviews other than as indication that I didn’t hit the restaurants filter button yet. Although, certainly restaurant menu prices are a lot more sticky than nightly hotel rates, there is no reason this tactic could not be attempted with restaurants. The real question raised by this comic, however, is if the erroneous signal sent by enough people operating in dick mode could be enough to cause the place to close, negating the benefit received by the dicks. There isn’t an answer to that yet, but I came across an academic paper today where “in ongoing work, [the author is] estimating the relationship between Yelp and exit decisions” of restaurants. Such information is crucial to answer the question of if the dicks are going to end up screwing themselves.

“Reviews, Reputation, and Revenue: The Case of Yelp.com” by Michael Luca of Harvard Bushiness School, actually finds that there is a correlation between the average Yelp review and restaurant revenue from 2003 to 2009 in Seattle. Actually, “A one-star increase [on Yelp] is associated with a 5.4% increase in revenue.” Yelp was introduced in 2005, so his data set can provide details about the impact of Yelp as it grew to become the dominant resource that it is today. He uses a couple randomization techniques allowed by the way the data is collected and presented to control for correlations between average Yelp review and other factors that may increase restaurant revenues, like having better food, to bolster his argument to the level of causation. The statistics are over my head, but it the theory seems solid, and certainly a lot of his assumptions ring true to my use of Yelp.

The paper brings up another interesting point that rings especially true. It finds that while overall, Yelp reviews correlate with revenues, that “chains already have relatively little uncertainty about quality, their demand does not respond to consumer reviews.” That is, reviews don’t matter for chains, maybe people don’t even read them. I said I was raised going out to eat. I was a picky eater and only child so going somewhere I would not fight about was probably my parent’s primary concern. That means that I was raised eating at chain restaurants, most notably Olive Garden. I believe that from when I turned five until I went to college I was at an Olive Garden at least once a month. If you include college, it might have to grow to once every three months. I still love Olive Garden thanks to all that conditioning, and when I go home to Ohio, I think I eat there within the first 36 hours, without fail. I have not once read a yelp review about the Olive Garden.

My dinner group essentially bans chain restaurants, with a couple of minor exceptions. That is likely one of a number of cultural reasons why, since moving to Boston, I’ve broken my Olive Garden streak. However, apart of my pilgrimage to Olive Garden upon setting foot in the state of Ohio, I seek out independent restaurants there as well. The paper also finds this is a trend much larger than my group. Specifically “chains experienced a decline in revenue relative to independent restaurants in the post-Yelp period.” Since ratings don’t matter for chain restaurants, but they do provide useful information on independent restaurants, there is a pretty good rational “that increased information about independent restaurants leads to a higher expected utility conditional on going to an independent, restaurant. Hence Yelp should … increase the value of going to an independent restaurant relative to a chain.”

With the power that Yelp has amassed of the past 6 years, comes skepticism, the specter of fake reviews, which I feared, and also the specter of intentionally false reviews as evidenced by xkcd. There is still another aspect of power that people take issue with, corruption or extortion of independent restaurants. Clearly, with the power to increase revenues drastically with a small shift in rating, there is an opportunity for yelp to offer to artificially increase rating at a cost to the restaurant, or extort from them with a threat of a lower rating. Enter this Davis Square Livejournal post:

I went to Paddock Pizza in Somerville on Sunday (not usually open Sundays, but there was an event) and I loved the pizza (plain). When I told one of the owners, she said she enjoyed it, too, but the first pizza chef, no longer there, got some bad reviews on Yelp and asked if I might be willing to put in a good one. I would in theory, but I’m not always much with the food review writing. Since I like their pizza and want them to stick around and keep serving it, I am willing to take someone who likes writing such things. (Their pizza is also pretty inexpensive, more so from 4 to 6pm (early bird specials), though they are only open Wed-Sat, 4-10pm). Message me if you are interested and are flexible-ish time-wise.

The text presented has been edited since my original reading. It originally included a line about “detesting” yelp, which was responded to in the comments, and caused a thread about Yelp’s abuse of its power, or at least perceptions of abuse, as no actual abuse has been proven. Here we have a restaurant which is aware of the power of Yelp to affect their bottom line, asking a patron who has expressed a positive experience to help them increase their rating. It seems the restaurant is acting fair in this transaction, they aren’t faking a review, they are merely attempting to turn a positive dining experience they provided into a positive review. Unfortunately for them, their pizza loving patron is not a writer it seems and is unwilling to jump through the hoops to become one because of perceived, unnamed abuses by Yelp. However, the crux of the post is that he is looking to hire someone to write a good review for this place for the price of dinner, presumably half a pizza. That must be some damn good pizza, maybe I should go check the Yelp reviews though. Every review since 2008, when the first review appeared has been >= 3 stars, arriving at a current rating of 3.5/5 stars. True, recent rating seem higher, but haven’t caused a upward trend in the overall rating yet. Verdict? Well no one has picked anywhere for Wednesday yet.